27/07/2022

Dr. Ewan Kirk on Do More Good – “We try and fund things that, if they work, can be a catalyst for a much larger change.”

Hosted by Kenneth Foreman and James Wright, the podcast focuses on professional development and fundraising in the charity sector. Its guests include charity leaders, philanthropists, and other individuals who are driving positive change through their charitable initiatives. At its very core, the podcast demonstrates the various strategies for doing good and showcases the people that drive it.

In this episode, Ewan discusses a multitude of things with Kenneth and James: his background in Cumbernauld; his various business experiences; his philanthropic philosophy; and even his multiple victories in the charity-fundraiser event Midnight Madness. At the heart of all this, Ewan stresses that experiencing failure can often lead to the most impactful insights.

Kenneth (K): Do something that's highly complex, but I think there's more that could happen there. So that's what I'd do if I had that, if one day we end up in that position. But let's get on and talk to someone who may be in that a similar position and talk to our guest. So, our guest this week co-founded his family foundation, The Turner Kirk Trust in 2007, and, since then, the trust has granted over £7 million to charitable causes across the UK and the developing world. The trust is an evidence-led multimillion pound family foundation that supports STEM, conservation and early child development causes. And it is one of the largest funders of fundamental mathematics research in the UK.

Now since starting his career in academia, our guest has secured a PhD in general relativity, founded and chaired multiple businesses – including Cantab Capital, one of the UK's first algo hedge funds, which managed more than £4.5 billion worth of assets and was sold in 2016 for $200 million. Since then he's carved out a niche as an investor in tech businesses, is chairman of Deep Tech Labs, which invest in start-ups that commercialise cutting-edge physics, and is executive chairman of Cardeo, a credit FinTech business. He's also part of the winning UK team that won this year's Midnight Madness Immersive London Challenge raising money for Raise Your Hands.

Now, Raise Your Hands is a charity that looks to readdress the injustice in the charity sector that sees the top 1.2% of charities receive 72% of the money donated in the UK. The challenge – which is unique in itself – sees teams compete a series of cleverly camouflaged and devilishly difficult puzzles throughout the night, hunting for and solving puzzles until they reach the finish line. So, we're really pleased to welcome Dr. Ewan Kirk to the Do More Good podcast! Hello, Ewan, how are you?

Ewan Kirk (EK): Very well, Kenneth. Hi – good to see you and James virtually, not in the pub, as you said, would have been the way of doing it prior to the pandemic. So, you definitely owe me a drink at some point!

James (J): You're not the only one – Kenneth owes a lot of people a drink!

EK: And there's only one change I'd like to make to your introduction: we didn't just win it this year – we won the year before and the year before and the year before.

J: Reigning champions!

EK: Reigning champions, yes!

K: Ewan, you've got to tell us more about this. I mean, I said when I was reading it, and obviously researching yourself, and I'd seen that you'd posted about it on LinkedIn recently, and then I looked at Midnight Madness and I'd never heard of it! And I've been working in fundraising in the charity sector and in events for the last eight years, and, actually, when I read it, I was like, “wow, that sounds pretty cool!” Tell us about it.

EK: So originally it was done in New York – a group of students from Yale did this midnight scavenger hunt around New York. And it got more and more complex and involved and sophisticated, and it got a little bit of a little bit of traction with the financial community in New York. So big banks would send in teams (you've got a team of maybe 8, 9, 10 people), and due to the fact I used to be a partner at Goldman, I was asked to join one of the teams well out after I'd left it. And it was just one of the best evenings I've ever had – running around Downtown New York solving complicated puzzles with a bunch of really smart people then running over to the next place. So they did it again in New York following year and I took a team – two teams, actually – from Cantab Capital partners over to New York to do it. And we nearly won, I mean really close, but I think the other team cheated! Then, for lots of reasons – because it's a lot of work – the people who put it together in New York just said, “we can't do it anymore”; and then Raise Your Hands and a group called Sharky & George came to me and said, “hey, we think we could do this in London. Would you like to kind of step behind it and help it start?” And I said, “sure!”

So, we had two teams in 2018, two teams in 2019 – we won both of them. And then, when we won the second one, the guy who runs Raise Your Hands introduced me as the smuggest man in London. and I said, “well, actually, probably Europe right now!” Anyway, of course, it's not something you could do in the pandemic. And it actually got rescheduled, I think, seven times! And then about a month ago, we did it again and it was just stunning. In this case, it was in east London, it was Canary Wharf, it was the…well, we ended at the O2 where they had taken over the O2 and we had to solve puzzles there. I mean, it is really quite geeky – and we talked about this before, as you know, I'm a little bit of a geek, but it's incredibly geeky. It's amazing fun. If you can imagine running around South London at four o'clock in the morning in the rain after you've been running for about 20 km or something, and everyone looking at each other and saying, “this is the best time we've ever had!”

And, of course, I love doing it, and I would love doing it if we didn't win, and I love it because of the event. But it is also an extraordinary thing for raising money – we raised the best part £600,000.

J & K: Wow.

EK: That's a lot of money, right? And a lot of that comes from the teams that were there from hedge funds in London, investment banks, I got together the Cantab Capital Partners team because that's now been marching into a different firm. So, I got together the team and we came back again to try and win one more time.

K: Well done – congratulations.

EK: It's a great thing to do. And it's a good example of a kind of innovative approach to fundraising. You know, of course, Raise Your Hands could just go out on the street and shake around a bucket and say, “give us some money”, but they really very cleverly identified that, “here is a group of people (the financial services community, or the technology community in London) who generally are not short of a bob or two. And if we do something that is suitably immersive, then we can get that money – we can open those wallets.”

I think it's really smart. I mean, it's a nice thing and £600,000 isn't going to solve world hunger, but, for Raise Your Hands, that's a lot of money and it goes to a lot of difficult-to-fund charities, probably because they're small. And that is one of the problems – that the big charities, the ones that we all know and love, they get almost all of the money. Is that a good thing? I don’t know. It's something that we can debate: should charity be much more concentrated and centralized, or should it be ‘just let a thousand flowers bloom’? I don’t know.

K: Yeah. No, it's, it's certainly an interesting debate. And, just to pick up on one thing there, I was going to say that James and I would love to get involved, but you said that you need really smart people. So, I think that kind of counts us out of it! But it does sound like a great challenge.

EK: Well, I'm just going to say that sometimes there's a moment of serendipity where it's not about smarts – it's just about going, “this must be the answer” and you don't work it out. I mean, there was a great example in the last one where – I'm not gonna go into the details of it – but the answer was ‘cat’ and one of our teams just said, “it's got to be cat. It has to be an animal. It's gonna be cat.” And we just said, “it's cat!” And they went, “yep! Off you go!” So, there are moments with serendipity where you just get it right and it's not about solving computer puzzles…let's see, sometimes it is!

K: I went to a pub quiz a few weeks ago and I sat there with…actually, I was going to say three very intelligent guys, but maybe there's two of them and my friend Dan, who won't mind me giving a call out. But, you know, we were the kind of guys that sit there at a pub quiz and we just wanted to have a couple of pints and have a chat and we must have answered two questions in the entire quiz. I mean, my dad was a bit of a quiz master – he loved it, but I'm an embarrassment to the family name when it comes to general knowledge and public quizzes.

J: Was one of the answers ‘cat’?

EK: now you know, Kenneth, now you know.

K: Look, Ewan, congratulations on an incredible career and your achievements, and everything that you've achieved in your career. I want to get into the conversation to take us back to the start. We see that you studied philosophy, astronomy, you completed your PhD, you studied in applied maths at Cambridge. How was that experience? And the question being, how did that set you up for what you'd go on to achieve later in your career?

EK: I think some of it is just a very analytical approach, a very evidence-based approach to anything. I mean, you can't really make it in astronomy, science, maths – whatever it is – without having quite an analytical approach to problem solving and being very evidence-based. To a great extent, that tertiary education that we do in the UK – degrees and masters and PhDs – they're all very much focused towards effectively becoming a Nobel Prize winner or a lecturer or professor or writing papers. And, due to the nature of the academic system, almost everyone fails, right? The number of people who win a fields medal is quite small compared to the number of people who do first year university mathematics, right? A very, very small proportion. So, all this training that we get creates this – nobody will like this phrase – but creates this exhaust gas that comes out of our university system, which are bright, smart people who have been trained in problem solving. And then they go on to be management consultants or lawyers, or in a lot of cases into finance – because that's a place where you can be a mathematician and people take you seriously, I guess is one of the things. So, it did quite a lot in terms of that analytic thing.

But, actually the one thing that I was just really lucky with was, when I was about 14, 15, 16, I got given a big bag of computer bits and a soldering iron and made a computer – and that started this love affair with programming computers. And, that was very useful for me in my research, but also, when you come out of academia and you go into the real world, what you need to be able to do is express your ideas. I was quite early in being able to program a computer well, and, in trying to be somebody quantitative in the world right now, you have to be able to program. You couldn't be a journalist without being able to write, you can't be a quant anymore without being able to program. So, I was quite lucky that I had that strength to my board and that really helped, particularly when I joined Goldman and we were right at those early days of the big bang and all this stuff growing, and you had to implement things to price securities to manage risk. It was all about just writing a piece of code. So that was the thing that really drove it, I think more than anything else.

J: Yeah. And you talk about bright, smart people coming out of university – you founded your first business in 1984 while studying for your PhD. That feels like a very confident thing to do at a young age. Did you feel that at the time? It must have been an exciting period, but was it just what you always wanted to do and that was the direction you were going to go in?

EK: I think I'll be brutally honest here and say, I thought I could make a bit of money. Because I didn't have any money! And I thought, you know, here's something that I'm reasonably good at – I can program – and a friend and I had this idea for something. And we sat in our bedrooms, programming up stuff and swapping around floppy desks and doing all of those things that you do. And we came up with something and then we sold it for like real money. When you don't have any money as I didn't, that was a big deal. That was a real eyeopener for me – you could do that.

It wasn't really the driver being, “oh, I want to be my own boss”, I mean, let's face it: I spent 15 years at Goldman Sachs with other people as my boss. So it wasn't just this desire to run my own firm; to be briefly honest, running your own firm is a giant pain in the bum – sometimes you're responsible for everything. But, it did open my eyes to the fact that you could be commercially successful and be that famous word, a bit geeky as well.

K: And where did that come from though, Ewan? I am guessing you were relatively young at that time, and I can't imagine there were a lot of…I'm sure you were kind of plugged into a bit of a network of other programmers, other geeks, if you like, that were trying things, but there's one thing kind of coming up with a product or designing something and then building a business about it and actually being able to market and then sell that business. Where did that element of it come from?

EK: I don’t know, I think you just make mistakes. You just try, you just experiment, you think, “oh, I've got this particular problem”. Let's pick a really prosaic one: you've got to create and file accounts once a year; do I know anything about accounts? Absolutely nothing. Right? So you just solve that problem by walking down the street and seeing a sign that says accountant, and you go in and you say, “hey, can you do my company accounts?” And some guy in a suit says, “yes!” And you go, “okay, here you go!” It's about that problem solving thing. And, you know, the original firm was small, and we sold some software and it seemed that it was a lot of money at that time (but not in absolute terms), but it was about solving the problem and being really quite focused on “what are we gonna do tomorrow?” In terms of, where did the geekiness come from, I grew up in Cumbernauld, literally the second shittiest town in the whole of the UK – according to a book that I once was given as a present, Crap Towns, Cumbernauld was number two on that list.

J: Wasn't Huntingdon number one on that list?

EK: No, I think it was Hull. Now obviously there's going to be people with pitchforks coming and turning up outside my house. But yeah, I don't think anybody from Hull or indeed from Cumbernauld would say that they are equivalent to, I don't know, Knightsbridge – they're not. And I went to what was at the time the largest comprehensive school in all Scotland with sort of 2000 pupils. And, you know, my little aphorism is I couldn't play football and I couldn't fight. So, the only way to actually do anything was to be a smart, geeky kid – be one of the dogs. And so, through that, you meet people you end up in a small group, a very small group from my school going to university. And then you just end up in that sort of milieu, and, before you know where it is, you meet obviously a guy saying, “hey, I program computers too, and I've got an idea and, you know, it's, it's not quite, you know…hey, do you play guitar? Hey, my dad's got a barn – let's start a band!” It's not quite that, but it's a little bit like that.

Nowadays, there is much more infrastructure and a much richer ecosystem around people who potentially have ideas. If you're at Cambridge university and you're a student and you've got an idea – it doesn't really matter whether it's tech or just a business idea – there's a whole ecosystem around you (like Cambridge Enterprise and to some extent Deep Tech Labs) that can take you through the whole process of taking this idea and turning it into a business. There wasn't really that infrastructure before. I mean, the idea of venture capital, start-up, I probably could have spelled venture capital, but I'm not sure I would've known anything else about it rather than that.

J: We could take this conversation into any number of areas as Kenneth touched on in that intro, but throughout it, there seems to be this motivation, this desire to do something good with your life and your time. Is there, is there something specific that sparked that? Has that always been there? Was there any kind of spark for that drive?

EK: You have to put this in context. I mean, with the best will in the world, I am not Mother Teresa. I spent 15 years as a partner at Goldman Sachs, the giant face-sucking squid. Then I was a hedge fund manager for 15 years.

K: I think that puts your CV out there when you applied for that job, right?

EK: Yes. Yeah, it does. I do honestly believe that we did good things in both of those roles, but they're not thought of as saintly roles in any way. And to be clear, a lot of the reason I was doing that was to…again, a phrase I’ve used a lot, I've been poor – I don't want to be poor again. And so a lot of the drive is I don't want to be poor again! But there is also that thing that at some point I've got enough computers, I've got a nice enough house, I've got a reasonable car, my kids are set – all of those sorts of things. There is a limit to what you can actually do, right?

J: What do you mean? As an individual?

EK: No, no for yourself, just for yourself, right? There's a limit to the sort of thing. I don’t know, maybe I could buy a boat. I mean, I hate the sea and I'm scared of the sea, and I don't like boats, but I could! But that would just feel like a little bit of a waste of time and waste of money.

So, at various levels throughout my primary two careers, I've always been involved in something or other that were giving money to charity very broadly defined. Now that was certainly a lot smaller back in the day, but it varies in size. I think you have to kind of pick something that excites or interests you. I'm sure we can talk about this, but I don't think that most charity can change the world. I don't think it does. Partly because it's too small, but there are ways of making very specific differences. Now, if you're a reasonable size charity, you could help a village in Africa, you could help kids in Cumbernauld be educated, for example. There's a couple of things, but once you've done that, that's all you've done. There are however many, 200 million kids in Africa; there's children all over the UK who are coming out of school and they're functionally illiterate or innumerate, which worries me even more. I can't solve that problem. If you're Bill Gates, that's different, right? I mean, Bill Gates, what he did fantastically well was actually think about how much resources he had and then sort of stack ranked or rank ordered all of the things that he could possibly put his money into and also worked out which of them was going to have the biggest impact. And it turned out to be malaria. Now in that case, he’s properly changing the world. There's not very many Bill Gates out there. So that does inform a little bit about how you think about philanthropy and how you think about putting your weight. And, as I said, we are not the Gates Foundation, but putting your own limited weight behind a certain number of things, what is that gonna be? You've got to think about it, you've got to be efficient. And what's the most efficient thing that you can do with that money, which can. Have an impact?

K: You've referred there a little bit to your kind of philanthropy and obviously you co-founded the trust in 2007, and, in some of the notes I think we were sent beforehand, you've given over £7 million to different causes and you talked about that you want to see fail. Can you tell us more about your kind of philanthropic philosophy within the trust?

EK: Yeah, it’s always annoyed me that, when you do a lot of travelling, you end up in lots of airport bookstores, and there's always that incredibly depressing line of business books. And they’re always…

K: James has probably bought a few!

J: I'm just gonna hide them. Yeah, let just move my…

K: Those ones right there!

EK: Yeah. Those ones. I don't have any focus back there, but I would just put them in the bin. But they're all the same! And they're all basically a biography of somebody who's been fantastical he's successful. Right? You know, how Bill Gates made it to be Bill Gates? How Jack Welch made to be Jack Welch? How Steve Jobs made it to be Steve Jobs, right?

J: Kenneth has yet to release his.

K: Maybe this is the time. The failed, unemployed podcast host. Yeah. Made it, made it.

EK: The problem is you don't actually learn very much from success because a huge amount of success is actually just being in the right place at the right time – just being lucky. If Bill Gates had been born 20 years earlier, he wouldn't be Bill Gates, right? Just because he was in the right place at the right time! Now I'm not saying that Bill Gates isn't fantastically smart and incredibly driven, a wonderful businessman, but he wouldn't be Bill Gates. And, I think it's always quite instructed for people who get to be quite successful to remember that probably you're successful due to luck. You're not just successful because you're such an amazing person. And I always wish that there was someone to go back to the airport bookstore. I always wish there was some book about failure, right? Because you learn so much more from failure than you learn from success! So, this sort of links into the philanthropic thing a little bit: when we were talking earlier, you were talking about want to give money to charity so that they can spend all of the money on doing good rather than spending on administration, paperclips, and so on. And that is a worthy thing; I'm not saying that it's a bad thing to do, but the problem is this focuses the giver entirely on the results, the doing good.

What's the canonical example? The donkey sanctuary. So maybe I'm really excited about donkey sanctuaries. I don’t know, I go to a donkey sanctuary and I say, “here's a hundred pounds or a million pounds” – it doesn't matter how much – “go and do good with donkeys.” And then the charity is sort of on the hook to come back a year later and say, “look at all the donkeys we've saved!”

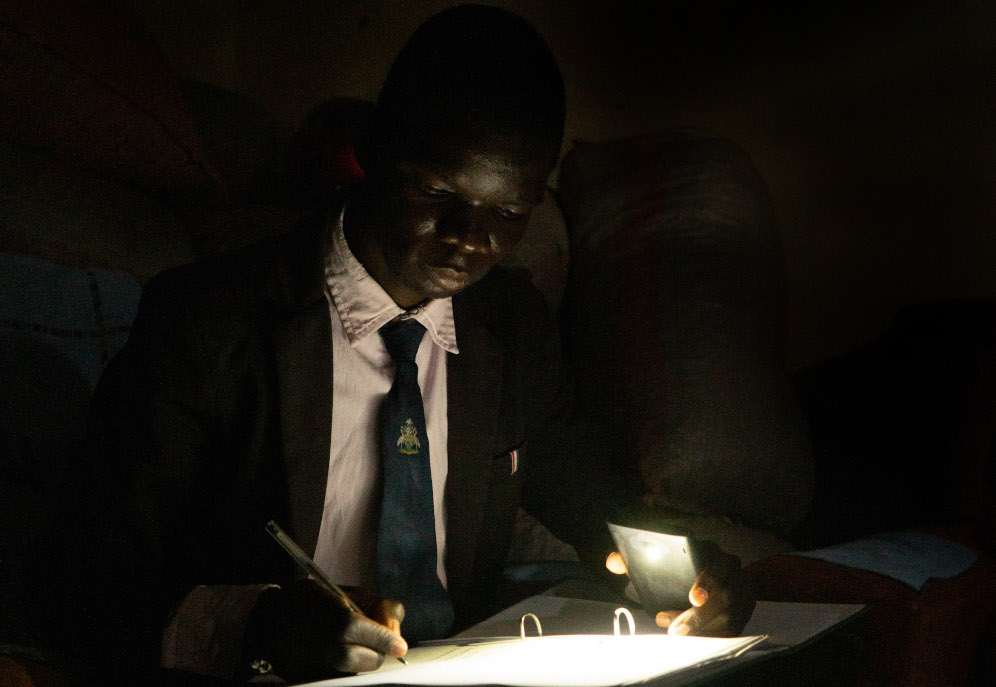

Maybe donkey sanctuaries aren't the best example, but that really discourages people from experimenting because they don't feel that they can fail. So we have the mantra, which is ‘Permission to Fail’. So we try and fund things that are first catalytic in the sense that, if they work, they can be a catalyst for a much larger change. And secondly, we almost encouraged the charities to experiment. The canonical example for us, of course, was SolarAid in Africa who could get solar lights, the usual sort of thing: a bit of solar panel, a light and two USB ports to charge a phone on, and they could get them into Africa, at some really quite small cost to get it delivered to the dock at Kinshasa or wherever, but they didn't know how to distribute them. How do you do that, right? I mean, do you sell them for like $10 or do you have a higher purchase agreement or should we just all be philanthropists and give them all the way? Because that would be a good thing – or maybe not.

So we just said to SolarAid, “here's some money, go and run five experiments in five different villages – and we don't care if all of them fail.”

J: that's so refreshing!

EK: If all of them fail, then you've learned something which is these five things are not the things that we should do. So that's one of the things that we try and build into most of what we do in that sort of experimental philanthropy.

J: It's Kenneth's turn to get the drinks in this week. So I'm gonna let you know that you can follow us on Twitter and Instagram at @domoregoodpod. Or, if you're a professional businessperson, you can find us on LinkedIn too. There's a website, domoregood.uk, packed full with episodes, blog posts, details of the team, and a link to the newsletter for your VIP content.

You're coming back! Two piña coladas and a lager for me.

EK: The other reason for doing this is that almost all the problems that charities face are government-sized problems. I mean, I've got some money, but I can't give a light to every single person in Africa. That's just impossible. So, what you need to do is create the environment in which you can do a pilot, a test, whatever that might be. Actually, we're in the process of trying to set something up in the west of Scotland to look at STEM education for underprivileged kids who are failing in that sense. Now, the trust can't afford to educate every child or give a light to every day, but if you can show that there's a sustainable solution…so here’s a way where this village of 500 people can get lights, they can afford them, and then they can feed the energy back into other things. And, ultimately, it'll end up producing money in two or three years time. You can then go to the Malawian government and say (this sounds like a big number, but it's a small number), “you can give everybody in Malawi a light and a mobile phone charger for $200 million and in 2 years’ time it will have paid for itself. Now that's trying to make that lead do something that can convince governments who have way, way, way, way, way more money than even the total amount of money in philanthropy to convince them to put their enormous weight behind making something happen.

So that's things like policy, obviously that's important, but it's also about whilst you can convince a charity that it's okay to fail because they're getting some extra money and it's if I'm willing to – and I'm doing quotes here – “waste it”, then the charity's okay with that. It's very hard to convince governments to do experiments because, you know, it's politics.

J: One charity perhaps could do that but, because we've set ourselves up to constantly re-reporting on good news and the achievements that we make, does the whole charity sector need to change to embrace that as a whole, rather than individual charities? Is that something you'd like to see?

EK: I think the charity sector needs to be a little bit more accommodating of firstly shooting for the boundaries, like properly going for something that might be completely different rather than just assuming that at the moment what they do right now is optimal.

The charity’s huge driver is a donor comes in or a potential donor comes in. And the driver is to say, ‘what we do is the best possible way of solving this problem’. Of course they do that. I mean, they're not going to go to a donor and say, “hey, well, we're not entirely sure if what we do right now is very good or not, but we'll keep doing it.” They've got that real driver to do that.

The other problem, and this is this brings in a little bit of a science problem, is that they don't report the null results. And null results are really important! I mean, it's a big problem in biochemistry research or medical research – if you do an experiment and you don't get a result, then you sort of don't report it. I mean, nobody's going to read a paper where people say, “I did this experiment, nothing happened”, right? But you should report that because then it stops somebody else doing the experiment!

K: I was just going to say there, Ewan, I spent three or four years, my first role in the charity sector, working for a medical research charity in Cambridge, actually around dementia. You might have come across them. But I recall, especially in medical research, when you're talking about a cause, such as dementia, we did talk often about the fact that we had to spend money on these PhD students at the micro level where the next big idea could come from.

Because it is a £25, 32 million charity, whatever they were by the time that I left, but we could never have the funds to bring a drug to market. But where we could have an impact is allowing PhD students, smart individuals, and fund at that level. But I do agree with your point that maybe we didn't make enough of that in terms of the failure, because we assumed that that would put the general public off when it came to funding: “oh, well actually, this charity is just spending my money on these students that don’t really know what they're doing”. But actually that's a critical area to find the next break!

EK: Yeah, there's a couple of things that come out of that. I know that group that you're talking about, and it has an emotional resonance for me in that my mother has Alzheimer's, so there's Alzheimer's in my family. So there is that thing where it has that resonance, but almost half the charitable money in the UK goes to medical causes – there's enough money going into that. And the final thing is it feels the…I am jumping around a bit, but your listeners all just have to stick with me, there's a fantastic German comedian called Henning Wehn and he says in Germany, “we don't do charity. We pay our taxes.” Alzheimer's is a big problem. We've got a big ageing population. It's going to become a much bigger problem. Doesn't that kind of feel like something that the government should be solving, rather than very well-meaning people putting in considerable amount of money into fixing that, into trying to do research into that problem? That seems like something that some political party should say, “we are gonna give £5 billion over the next 10 years to an Alzheimer's Institute and we're gonna solve that problem. Do you want to vote for me?” It feels like the right thing to do – I think. Rather than you, Kenneth, I'm sure you were fantastically good at raising money, but I bet you didn't raise £5 billion.

J: It was just shy. Wasn't it? It was four. Yeah – it was four. But no, that's a great point, that's a great point: The scale that a government can make a difference is huge.

EK: Well, I mean, Henning Wehn is definitely making fun of Germany as well as making fun of the UK, but it does feel like something we should have a discussion about in terms of what is the actual for charity. I don't mean we should have a discussion and I'm sure we’d have a possibly good discussion, but I don't want to use the word society, but, as a country, whatever it might be, this is something that we should discuss as to where the line is drawn between charity and a societal goal. And I think medicine is a difficult thing because there's obviously a lot of long-tail diseases where not very many people get those diseases and, therefore, they don't get any research funding. And I know that, from a rational perspective, that makes sense, but it doesn't make sense if it's your kid.

J: A personal level – yeah.

EK: At a personal level. But so those lines where it gets much, much harder is when you move into things like education and housing and training, where it sort of feels to me, like those should be the per view of a government, not a charity. But you can definitely have disagreements about that, but I think it's a topic that we should least discuss more.

K: Yeah – more often than we probably do at the moment. I want to just move on, Ewan, in a little bit to your role in terms of being the co-founder of a charitable trust. A lot of our audience obviously work in the charity sector, we try to go a bit more broad now, all four of them are now – we've got someone from somewhere else – but, can you just tell us what that’s like in terms for you being the co-founder? How much day-to-day involvement do you have? What does that role look like for you? Can you give us any insight into that?

EK: Sure! We did set the trust up in 2007, as you said, but I was pretty busy, you know.

K: Building computers, weren’t you?

EK: Yeah, yeah. Building computers, running a hedge fund, and my wife was also very busy doing what she does. So it was all a bit sort of unstructured. I don't know, I'd be at some dinner and somebody would be raising money for a mini bus to take kids to the Lake District and I go, “here's a check.” Right? “Never talk to me again. Bye.” And there was just lots and lots of that kind of stuff. Sometimes we locked into some really important things, but we didn't really think about it very much. So after I'd moved on from Cantab and had a little bit more time, because I've got a portfolio life you're doing lots of different bits and bobs, and we consciously took the decision to make things a lot more structured and to try and have some broad goals. I mean, there's obviously the ‘Permission to Fail’ thing, my wife's very into conservation and early childhood stuff and she focuses on that, I also quite like very high-end STEM – so, we've funded fellowships at the Isaac Newton Institute for people traditionally underrepresented in the mathematical community, which is mostly actually women and is a big problem. So within that framework what we've tried to do is just be a lot more rigorous about identifying the things that we can fund, looking at them through the lens of ‘Permission to Fail’, looking at them through the lens of “let's be a catalyst for change”.

And what that actually means is you see ‘no’ a lot more often – and that's really hard. I mean, obviously there are some things that I would maybe never say yes to, but there's also a lot of things that I would really like to say yes to but they just don't fit what it is we want to do. And so you've got to say no, and you've got to say no to people for whom this is their life. I'll use the example of donkey sanctuaries, even though it’s a hypothetical example…

K: You know you're going to get millions of requests from donkey sanctuaries after this? “I've got a really innovative donkey ride that I'm gonna put on this on this beach.”

EK: I'm not actually dissing donkey sanctuaries. I mean, it is an important thing and people are allowed to be passionate about things like that, but I'm not passionate about it. But you're turning down somebody who is really passionate about the thing that they are passionate about, right? It's a tautology. And that's quite hard, but, if you don't do that discipline, then you just end up doing lots of little things that don't really make any difference. Now one of the things that having a long career in finance taught me is A – that nobody really knows what they're talking about. And B – neither do I! So to put that in a little bit more of a less aphoristic framework, it's about uncertainty: you've got to have some understanding of your own lack of ability to forecast and to really know what's going to happen. So sometimes, what we've got to do is sort of embrace that uncertainty and say, “let's go and do things that might fail!”

Just a couple weeks ago, I was up at Glasgow University for the first time in a very long time being shown around by their philanthropy group and going seeing cool stuff like quantum sensing and space rockets and all sorts of unbelievably great stuff. But what I had to do is force people to say, “yes, I know this is all great, but what's the experiment that you would do that you think, if it succeeds it'll be transformative, but you think it might fail – what's the experiment you do for that?”

J: I bet they don't have an answer to that, do they? They can't be challenged in that way. I mean, there can't be many philanthropists with that sort of outlook, and, as you're talking, Ewan, (as we mentioned in the introduction) obviously you've been around the kind of VC fund, you've managed a hedge fund, your investment in tech, your philosophy for that type of business sounds like it applies also to your philanthropy. Would that be a correct? Not in a similar fashion, because I know they have different objectives, but would that be a fair statement?

EK: It's not that different. I mean, for something like Deep Tech Labs or something like the hedge fund – we were a systematic hedge fund, so 60 mathematicians, physicists, computer scientists writing computer code dimly forecasting the market – and if you're right 52% of the days and wrong 48% of the days that is knocking the ball out of the park. There's a huge amount of uncertainty. And it’s the same thing in the venture world. However many companies we fund at Deep Tech Labs I think will be quite good, but probably 3 out of 10 of those will just fail. Just go to zero. It's just not going to work and all you're trying to do is to just shift the odds. You can't go for certainty. What you're trying to do is to use that mathematical thing, and I'm also waving my hands around here which isn't going to show up on a podcast obviously, but you've got this sort of bell curve distribution, and, rather than trying to sort of pick the right-hand tail, all you are really trying to do is just move the whole distribution to the right a bit. On average you want to be a bit better and that was how we thought about things at Cantab when I was running it and it's also how I think about my own investment, how I think about venture capital, and, to an extent, how I think about philanthropy – that it's about trying a few things. Obviously you want to get the right-hand curve, the really transformative thing, but mostly it's about on average doing a bit better.

J: When you say you have to say no to people a lot, that must be tough and it must be difficult when things don't pan out and they're the 3 of the 10 that don't work. But for those that do, for those that really fly, you put some investments somewhere and it really works, that must be amazing to see that – you must really enjoy that.

EK: Do you mean in philanthropy or…?

J: Well, I guess in philanthropy, perhaps, but yeah, I guess in both!

EK: There is nothing like being a small part, even if it's just a funding part, of something being successful. It's not in the same way as I am super proud or maybe even a little smug about the fact that we won Midnight Madness three times – see, look, I've got that in again. It is not that kind of feeling right. It's the fact that just watching other people be successful and going through that process from having an idea to coming out of the other end going, “it works! Woohoo!” Just watching people do that is a real joy – it really is. And, you know, the other thing that you have to do when you do that is, of course, some people fail and you have to be able to be around when it's not going very well and it's all fallen apart, and you've got to say to people, “look, maybe this just wasn't the idea; maybe there's another idea. Go back and try again, stand up and give it another go.”

J: And I bet that approach – I mean, I have no science to back this up – but I bet your approach of saying, “go and try – it doesn't matter if you fail. I don't necessarily need to see the results. Take the pressure off, try stuff!”, that is going to result in far better tests and better experiments and more success in the longer run than it does if you say, “right, we're gonna give you some money and I want to see X” – really put the pressure on for results.

EK: Yeah – and there are lots of things which you just can't put pressure on for the results. There are some bits of research, some types of very deep technology companies, some types of philanthropy where there's no lever that you can just push which says, ‘work harder, be more successful’. There isn't that kind of thing. It's got to take the amount of time that it takes to get it done.

J: That's what Kenneth does to me. Yeah – hits me with sticks if we don't get the edit going quickly enough.

K: Work harder, James, stay up till seven. Stay up all night. Get it done.

EK: Stay up all night and get it done badly. If you're editing mine…

J: Oh, you have listened to episodes!

EK: If you're going to edit mine, James, make sure you have a good night's sleep so that you edit out all the rubbish.

K: No, it's brilliant. Ewan, and we will start to wrap it up. I mean, I'm sure we could sit here and explore so many different topics – and you've touched on them before – but I guess the final question thinking about wrapping it up is, from your philanthropy side of things, you know, we're a podcast that's around the whole area of “do more good” and we've taken some criticism for our name of ‘Do More Good’. Like what does ‘Do More Good’ mean? But we came up with that in a pub. But if you've got any better suggestions, we're open to it.

EK: How about ‘Do More Good On Average’?

J: 52:48.

K: That's the ITV2 episode, isn't it? But what's your hopes for the future? We’re sat here in 15 years’ time – is there anything you’re thinking about that far ahead? Is there anything that you hope that you've achieved through your philanthropy in that time?

EK: That's one of these really difficult questions. Of course, you go through life not really thinking about things like that and sort of trying to plan stuff ahead. I used to say when I was running my own firms that my long-term strategic goal was to not go bust next week. That is a little bit of a caricature, but I do feel that there are of course times where if you do – what we would say in mathematics – the locally optimal thing at all points, you end up in the wrong place, right? You don't end up at a global maximum. But mostly if you do the locally optimal thing – if I just do the right thing this week, do a nice podcast with two nice guys, have some board meetings, go out on my bike, do whatever it is – that's locally optimal for me right now; do some reviews of some philanthropic projects that people have done, make some decisions, do that, and then next week, I'll just keep doing that again. And if I just keep doing that, then probably not a hundred percent, but probably I'll end up having done some good things over a week, a month, a year, 10 years.

I think that's one way to think about things. It's quite hard to have a long-term vision because…there’s one quote that I use all the time and it is that Mike Tyson quote, “everyone's got a plan until I punch them in the mouth.” And that does say something about plans, right? You're going to get punched in the mouth. So why don't you just make sure that what you're doing is good at any point and then see where it leads you?

K: Perfect, perfect. I like that – I like that a lot. Ewan, thank you. We're not going to let you go straight away. We always have three questions that we drop into our end of our…

J: This is the punch in the mouth bit, isn't it?

K: This is the punch in the mouth.

EK: Damn!

K: Um, James, do you want to…?

J: I'll go first. So, cool! If you could transport back in time and meet your 20-year-old self, what piece of advice would you give and why?

EK: Oh, wow. Keep on with the computer programming because it's a good thing. I'm allowed more than one piece of advice, right?

J: As many as you like.

EK: What I would say is there will be a time where you will look at a firm called Apple and think they are a stupid firm and they will never make any money. When you do that, do not believe yourself and just put all your money into Apple. So that would probably be two pieces. I'd also…I mean, I did well on this, but I would remind myself that, when you have kids, they are the best single thing that happens to you and it ends faster than you think: before you know where they are, the little girls (in our case that you had) that were running around being little girls, before you know where they are, they're grown up and you think, “oh man, I wish I'd had twice as much time.” So that's the thing, family is very important.

J: I have a bit of a follow up question – which we haven't done this before, Kenneth – but a follow up question: would your 20-year-old self have listened to you?

EK: Oh, probably not. I was a bit of an idiot then – so maybe not. I don’t know, that's a good question. And I know we do all kind of change over time, although strangely not as much as you might think. Now, when I was up in Scotland, I met somebody that I hadn't seen for 35 years – a lot has gone on in both of our lives in 35 years. And we went out for dinner and it was like it was yesterday. So maybe the me now was always inside the me then. Yeah. In some way, I don’t know, that's a really hard thing to say. I'd like to think that I was smart enough to do that, but I probably wasn’t.

K: Okay well, Ewan, thank you for being the first person in over a hundred episodes to say, “James, that's a good question.” So appreciate, appreciate that one. Okay, second question: can you tell us about one life hack, a productivity tool, a habit, or a skill or something that you've taught yourself recently that you think everybody needs to know about?

EK: Oh, God. I mean, my life is just full of little, tiny hacks to make things work a little bit better. You know, I now have what could in some lights be seen as an amazingly obsessive way of making coffee in the morning where I've cut it down to the absolute minimum number of movements required to make two cups of coffee – one black, one white for me and my wife. And if I walked to the fridge with the coffee steamer, that would be one less journey. So over-optimizing things – I mean, there's lots of examples there because, you know, I am to some degree on the spectrum. I mean, trying to make six pieces of bacon fit in a round fry pan precisely – there's lots of different ways to do that. I would say, it's one thing I do try to do – and this is not really directly applicable to most people – every year I teach myself a new computer language, a new program language.

K: Wow!

EK: Because it keeps me current! I learned one this year with an app and it keeps me up to date. And, the one thing I would do is find something that you can continuously learn at.

K & J: Yeah, that's great. That's nice!

EK: Yeah. So, whatever it is, I mean, it might be,

K: Golf – golf in my situation.

EK: It definitely would not be golf for me, but something intellectual as well, not a physical thing. So not something that can be done! You know, I don't care if you're obsessive about 18th century Italian opera…

J: How did you know?!

EK: Find something that you just continuously learn doing and that you really focus on. I think that's good – it's a good thing for everyone.

J: That and fitting six bits of bacon into a fry pan.

EK: Yeah, that's really important. And when you take them out, you've got to fit on the piece of bread. I told you I was a little bit on spectrum!

J: Very good. Final question for you. As a podcast, it's focused around people doing more good. What's your favourite story or inspiring individual you have met on your journey (or recently) who has done something good for others?

EK: Oh, wow. That's really hard because, I know I probably shouldn't do this, but I might just pass on this because I'm not really sure I want to single somebody out. But if you really force me and you did see recently the guy that runs Raise Your Hands, Ed, it has done an amazing thing.

I mean, firstly, he brings joy to 200 geeky men and women once a year doing puzzles and stuff, and, actually, the guys at Sharky & George as well, but they do that entirely selflessly, and they work like unbelievable hours to try and get this incredibly immersive experience. It takes them all years to do it and they're doing it because Raise Your Hands is their passion and what they really want to do. So, yeah! I mean, would I have that dedication to do that? No, I didn't think I would. So there you go. That's what I would say in recent past…I mean, there's probably others, but you did put me on the spot and you didn't…

K: I know it's a horrible, horrible question. See people where people are like, “oh my god”, because, of course, part of the reason – like we were saying before we started recording – is you meet so many brilliant, amazing people in this sector and in life generally. And you know, particularly through this! And so when you put people on the spot like that, and every person they've met in the last week flashes through their mind, or the email that they read, or the last thing that they read. So, yeah. Look, we appreciate it's difficult. Oh, there's the dog! It's walk time! That's the perfect cue.

Ewan, thank you so much for your time. We really appreciate it. It's been fascinating to hear your background and your story and your approach and philosophy – and we wish you lots of luck in it! Good luck and please keep doing the amazing work that you're doing!

EK: Well, I will do my best and I'd just like to say this was an absolute joy. I mean, it was really fun and a little bit weird. But, there are enough non-weird podcasts out there. And I think, I think you guys are doing a fantastic job, so well done! Thank you very much! Maybe I should have used you, you two, as my example of people I've met recently who were doing good.

K: Ahh, we’re sat right in front of you as well!

J: Kenneth's even holding a sign like, “pick me!”

K: James, any final thoughts?

J: Uh, final thoughts for me? Uh, I need to cancel my Airbnb in Cumbernauld for a couple of weeks’ time. And maybe we can spend that week writing our failure novel for airport libraries. That will make us millions.

ENDS